Harvard economics professor Claudia Goldin made history when she won the coveted Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences alone, without having to share it with a fellow scholar. We’ll examine Goldin’s incredible accomplishment and the factors that led to her being given the Nobel Prize in Economics in this blog article. It’s crucial to remember that Goldin has been a trailblazer in the area of economics for many years. Her work has helped us understand and solve fundamental issues like gender inequality, labour force participation, and the gender wage gap.

The U-Shaped Curve: Rethinking Women’s Labor Force Participation

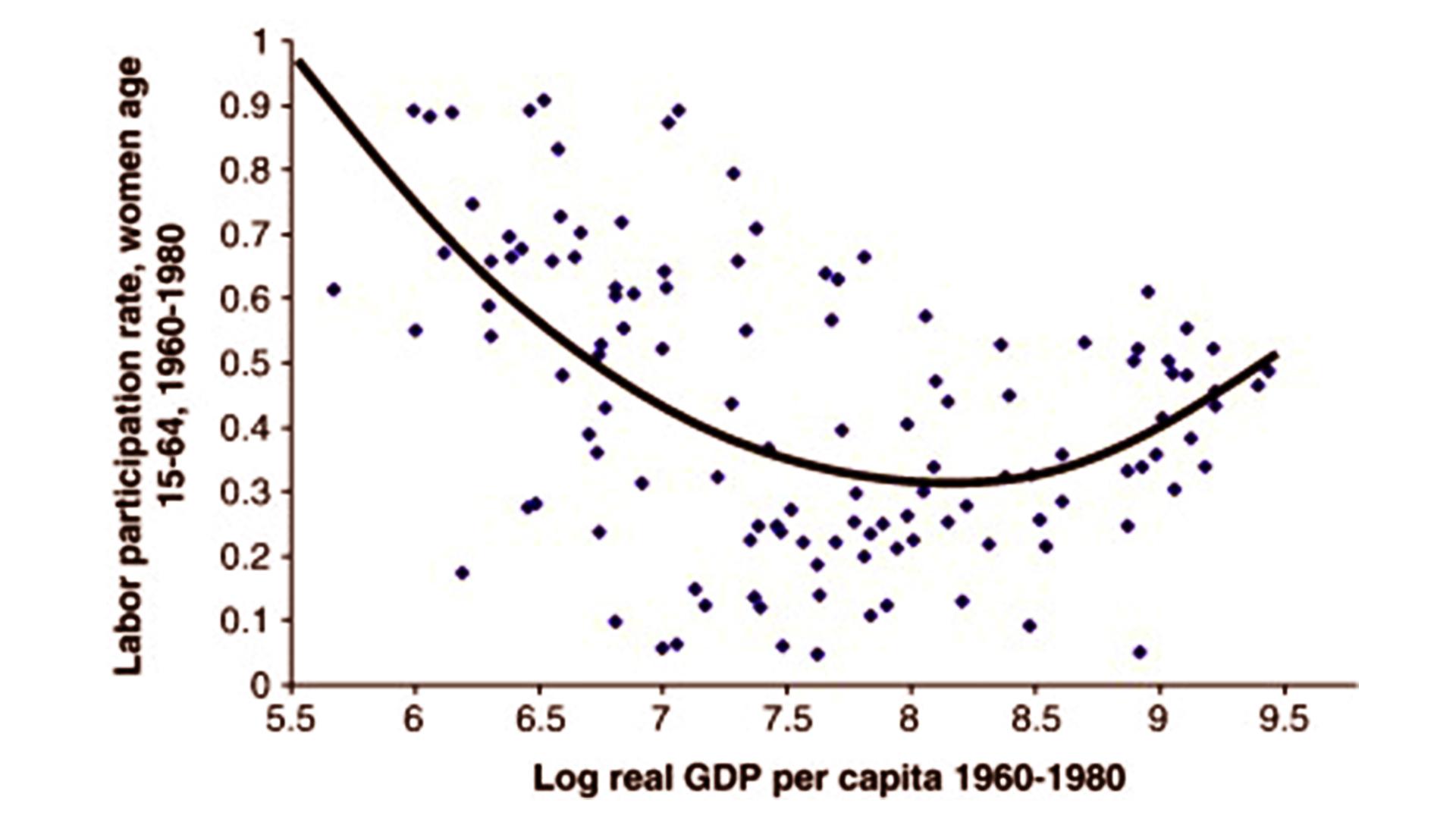

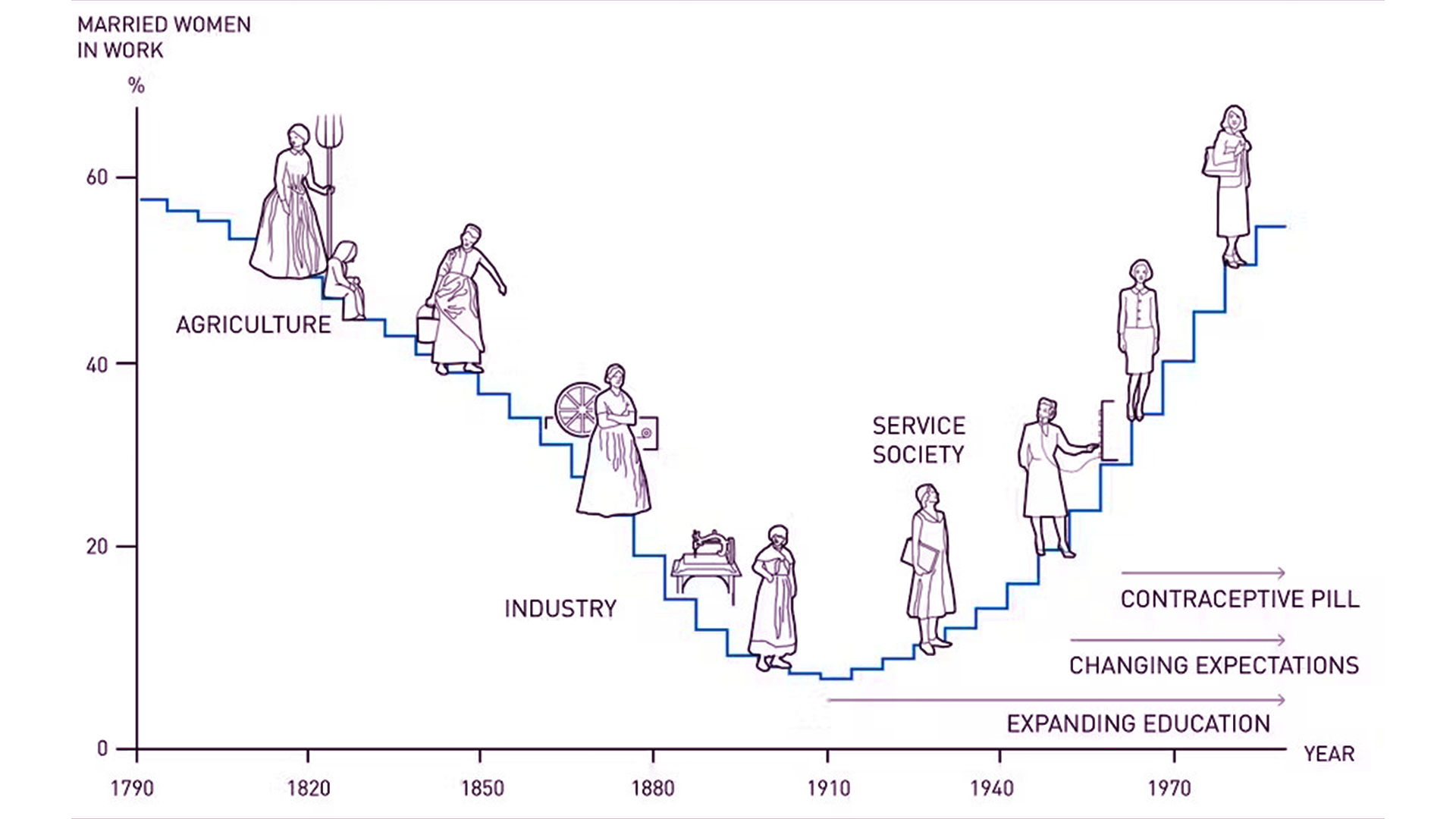

Claudia Goldin’s reassessment of the connection between economic development and women’s labour force participation is among her most well-known contributions to economics. Before her work, the general consensus was that the number of women entering the workforce would increase in tandem with economic growth, resulting in a straight line. In 1990, Goldin refuted this idea, demonstrating that the connection in the US followed a U-shaped curve.

Because many surveys had disregarded married women who were frequently categorised as “Wife” without taking into account their contributions to labour, notably in agricultural operations or family enterprises, Goldin’s research exposed serious inadequacies in historical data sets. The labour force participation rates were three times higher when these women were counted in the statistics.

Industrialization, which forbade women from working from home and forced them to labour in factories, made it difficult for them to strike a balance between work and family life, and thus contributed to the fall in women’s labour force participation. Social norms and expectations that restricted their work prospects posed significant challenges for married women.

Changing Expectations and Educational Choices

The belief that women would abandon the workforce after marriage affected women’s educational decisions in the early 1900s. Many women thus chose educational paths that might not have been consistent with their long-term professional goals. But by the 1950s, career prospects increased and social standards started to shift. Still, young women made their educational decisions based on antiquated notions.

The main change happened in the 1970s when more high school courses focused on college preparation were taken by young women in response to the changing environment. They became more proficient in arithmetic, went to college at a higher rate, and choose majors that are often associated with males. There was also a rise in the median age of marriage from 22 to 25, which Goldin called a “quiet revolution.”

The Role of Contraceptives in Empowering Women

The invention of the birth control pill, or contraceptive, was a significant advancement that further boosted the participation of women in the labour force. Women now had greater control over their bodies because to this invention, which allowed them to put off getting married and starting families. Alternatively, individuals might put money into their jobs and education. Although this theory was generally accepted, Goldin was the one who carried out extensive study to prove that women’s job decisions and the availability of birth control were causally related.

The story around women’s labour force participation was rewritten by Claudia Goldin’s study, which emphasised the crucial role that women played in economic dynamics. In addition to pointing out historical problems, she offered insightful commentary on current concerns that affect gender inequality and the gender wage gap.

The Gender Pay Gap and “Greedy Work”

Although there has been progress in certain areas towards gender equality, there is still a gender wage disparity, especially for women who have children. Goldin tackles this problem in her most recent work by presenting the idea of “greedy work.” According to this hypothesis, workers who put in more hours are compensated disproportionately, receiving higher wages than the extra output they provide. If you work twice as many hours, you are paid more than twice as much; yet, if you work half as many hours, you get paid less than half as much.

The problem emerges when women who have children find it difficult to dedicate as much time to “greedy work” because of their childcare obligations. This contributes to the gender wage gap by placing a heavy cost on women who cut back on their work hours to meet family obligations.

Furthermore, Goldin notes that if families choose to evenly divide childcare and domestic duties, both partners may need less challenging occupations, which would mean lower family wages. Thus, a 50/50 split of responsibilities may result in happier marriages, but it may also cause financial difficulties.

Claudia Goldin won the Nobel Prize in Economics for her outstanding work bringing attention to the importance of flexibility in women’s earning potential as well as for her thorough investigation of the many variables influencing gender inequality, labour force participation, and the gender pay gap. Therefore, in addition to revolutionising the discipline of economics, her work has been essential in increasing gender equality in the workplace.

0 Comments